Are the modern too acclaimed?

Modern and contemporary Indian art is playing a major role in the art market. It has a growing presence in museums and institutions, with exhibitions and records of all kinds for these established artists. Certainly stronger than Chinese art, which often proves to be the result of pure speculation, the Indian art market is succeeding thanks to its quality and its history. We’ll keep 1947 as a baseline— the year of India’s independence and the creation of the Progressive Artists’ Group (PAG) of Bombay whose founding members, M. F. Husain, F. N. Souza, K. H. Ara, H. A. Gade and S. K. Bakre figure among the founding fathers of modern Indian art. Succeeding the Bengal School, the PAG developed a new visual language and identity which made it famous. Prior to Tuesday’s record-breaking sale, Birth, a 1955 work by F.N. Souza sold for $4,01 million in New York this September, a record at that moment, driven by these results, Christie’s intends to maintain its lead in sales of Indian and Asian art through innovation. Deepanjana Klein, head of the South Asian Modern & Contemporary Art department at Christie’s, spills the beans on the auction house’s plan for 2016: “What we want to do at Christie’s, is to find new talent: go to Pakistan, go to Sri Lanka, go to Bangladesh, and India…find these talents and launch them.” There are certainly a whole host of collectors excited to discover and collect the artists tapped to become the next Subodh Gupta.

Collectors buying on a whim

American collectors from Nebraska, Karen and Robert Ducan, own over 2000 Indian artworks, their collection is considered to be among the Top 50 in the US, according to Richard C. Morais speaking to Barron’s. Whilst Czaee Shah, a pioneer who defines herself as “the only true local contemporary art collector,” estimates there are only about 25 serious collectors in India. However for those who don’t have the means to acquire works by the big names in the Indian market, there are a growing number of galleries offer new talents on the brink of becoming future stars.

Future stars in the making

Young Indian artists are making a name for themselves internationally too, American collectors, the LeBarons, have acquired Divine Death, a painting by Ratheesh T., for $34,000 from Mirchandani + Steinruecke gallery in Mumbai. Born in 1980 and living in Kerala, Ratheesh T’s paintings are as much naive art as dreamy fantasy. His monumental frescoes also recall a complex and universal symbolism. He was first known by way of his 2011 solo show between Michael Haas gallery and Mirchandani + Steinruecke he also recently participated in the 4th Fukuoka Triennale in 2014.

Vibha Galhotra, a conceptual artist whose thinking is centered around the world’s changing topography due to globalization and disproportionate growth, is also capturing attention. Concerned by the pollution in New Delhi, she recently joined forces with Chintan Upadhyay and Anish Ahluwalia who, with The Bovine Divine, put the danger of plastic invading cities in the spotlight. It is also worth noting the rise of Shine Shivan (born in 1981) who turns plants into eroticism and blurs genres, as in his series Sperm Weaver (2009).

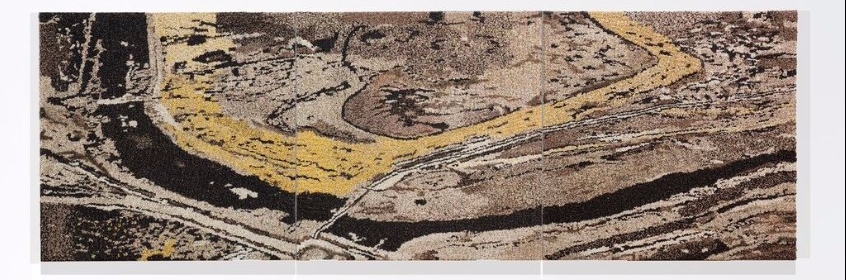

Rateesh T, Ganga (2014), private collection

Elsewhere Sri Lankan artist Priyantha Udagedara (born in 1975, now living in the United Kingdom) who was profoundly marked by the civil war in his country, is an artist to watch. In his PhD dissertation on Rediscovering Paradise, the artist explains his work as a search for a new landscape that would bring terror and beauty together in one place.

Rateesh T, Ganga (2014), private collection

How the Online Art Market can help?

After a round-up of the online art sales, which has grown to account for 2.7% of the overall sales, the report is a bit reluctant about the actual disruptive impact of these technologies.

“One might be led to wonder whether the frenzy of activity of the past few years surrounding the online art space might not have subsided or reached a plateau of maturity, without much disruption having occurred, as anticipated to the traditional sectors. ‘Disruption’ and ‘democratisation’ were the two most promised outcomes in the art market by many of the newly emerging online companies. However, for the most part, the majority of online players are just doing the same thing online that is already being done offline, with the new online channel complementing traditional offline channels” (Andrew:55)

A counter-argument to this feeling of deflation with the promises of the online art sector is to consider the potential for disruption in other ways. As mentioned in the report, the market spends an estimated $17.8 billion on a range of external support services directly linked to their businesses, with spending increasing 3% year-on-year despite the decline in sales in the art market. This supported a further 330,353 jobs (Mc Andrew:17) – and how could the art world’s ancillary services be disrupted by technology? Companies like Artbinder, Collector Systems, Collectrium, Trov, Articheck, Artlogic, Artrunners and even ourselves are disrupting the status quo on the ancillary services to the art world, and there are many ways this could keep growing in the coming years. One of the major data sources for this report, Artnet (whose CEO Jacob Pabst will also be speaking at the symposium) has built a reputed publicly listed company on servicing the art world.

China as a transparent global powerhouse

China is a huge market for our company and generalisations never work well. Read the data about China carefully, as the headlines can be deceiving and more information is available in the more detailed descriptions later in the reports.

The Chinese market is reportedly down by 23% in value (Mc Andrew:23, Mc Andrew:31), but this is deceiving with strength of the market in the UK and US largely being supported by the Chinese (and Russian) buyers. There is indeed an issue with non-payment in China, with many lots not paid for, but major auction houses outside China have reported “increases in Chinese buyers’ expenditure of 50% or more” (Mc Andrew:36). The decline this year is also partly to do with China’s anti-graft campaign, which might cause a temporary slowdown but will help the market be stronger in the long run.

Another reality check to the Western-centric art world is that there are many ‘superstar’ Chinese artists that are attracting a lot of attention and China is eager to start having more bilateral collaborations and see their artists shine within and outside the country. So museums, as you work to bring your Warhol or Constable exhibitions to China, think about bringing over exhibitions of Dong QiChang or Qi Baishi over to the US and Europe.

Priyantha Udagedara, Paradise Lost III (2011) | Courtesy Saskia Fernando gallery, Colombo

Mass versus Master

There are some very poignant statements in this year’s report about the shrinking middle class. Though it is a common theme in all economic reports the last few years, it is particularly pronounced in this year’s statistics.

“The top 10% owned 88% of the world’s wealth in 2015, leaving 12% distributed across the remaining 90%. Some of the greatest levels of wealth inequality are currently found in countries such as the US, Switzerland, Sweden, Russia, India, Brazil and Indonesia, where the share of wealth owned by the top 10% was greater than 70% of the total.” p. 189

The shrinking middle class can have repercussions on the museums and exhibitions sector, meaning that the stellar content is reserved within a small circle. Sales to museums and other public institutions were 9% of dealers sales (1% down on 2014), while corporate sales were again the smallest portion. (Mc Andrew:216) This means that works are being taken away into hidden treasure troves, and museums will have to really work hard to get the works onto their walls. And the ones who ultimately suffer most, are the general public. We must work hard to incentivise owners of these important heirlooms of our world’s history to make them accessible to the general public.

As highlighted during last year’s symposium ‘Private Going Public’ – if you read between the lines, it seems like the public sector has a major role to play in the art market going forward. Both the art market and the museum sector can benefit from the mutual collaborations, by working together to strengthen each other’s industries. The market is cooling, and a collapse can only be averted by adding actual value to the market.